Tom Jones ’88, a UW professor and artist, moved around a lot as a child. He started out in North Carolina where his father, a photographer and painter, worked as a regional manager for Kodak. Jones and his family had lived in Orlando, Minneapolis, and Orlando again by the time he was a sophomore settled in Madison. He had two things to anchor him: his Ho-Chunk heritage and art.

Despite the frequent moves, Jones developed a strong connection to his culture, fortified by summer visits to Black River Falls — the seat of the Ho-Chunk Nation — and his mother’s dedication to Ho-Chunk values and traditions. JoAnn Jones ’82, MS’83, JD’86, the first female president of the Ho-Chunk Nation, made sure that her children took part in their culture no matter where they lived. When she enrolled at UW–Madison, she brought her family to an area rich with Ho-Chunk history — a place called Teejop, or “Four Lakes,” long before it was known as Madison.

But for Jones, art, not tradition, was the key to feeling at home in Madison after an initial culture shock. He wanted to drop out of high school but leaned into his art classes instead. “I can’t remember there not being art as a part of my life,” he says. As his mother finished her education at the UW, Jones enrolled to pursue an art degree and train as a painter.

When Jones began graduate school at Columbia College in Chicago, he switched to photography “because of the immediacy of the medium.” He used his camera to capture images of effigy mounds in Wisconsin before giving up his battle with uncooperative weather. “I turned my camera to the elders of the tribe,” Jones explains. “The trajectory changed, and I have not looked back.”

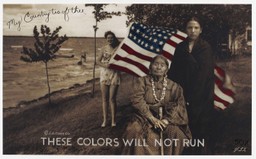

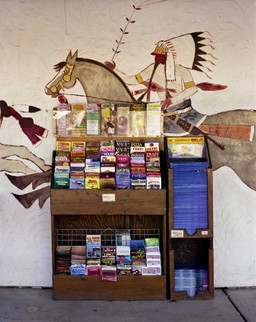

Jones’s work has since focused on Native American identity. As a member of the Ho-Chunk Nation, he’s able to share an Indigenous perspective from the lens of an insider. Jones’s many series show different sides of the Native American experience: portraits of relatives and fellow tribal members in traditional regalia; shots of memorabilia from fallen Native military service members; historical images of Indigenous people juxtaposed with the lyrics of “My Country, ’Tis of Thee”; pictures of tourist areas that commercialize Native culture with souvenirs and advertise with Native imagery.

His latest work features subjects against a solid black background, which he fills with intricate beading. A single piece can take more than 100 hours to complete. “The beadwork is a metaphor for our ancestors,” Jones says. “I’m drawing on inspiration from Ho-Chunk beadwork, silk applique used on clothing and blankets, and old twined bags.”

Jones’s work is currently displayed in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, and in Water Memories, an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. In October, Jones wrapped up his work at the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago as well as a major retrospective, Here We Stand, at the Museum of Wisconsin Art in West Bend.

Get a glimpse of his art below, and find more of his work and information about upcoming shows on his website.