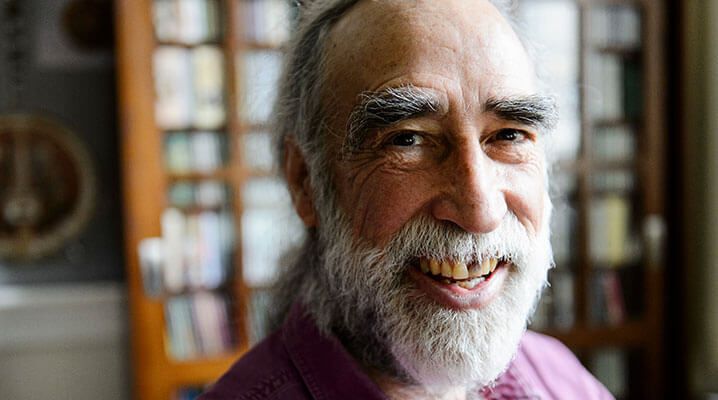

Jim Leary is a professor emeritus of folklore and Scandinavian studies at UW–Madison and an expert on the folklore and culture of Upper Midwestern and Wisconsin people. “Every place, in its own way, is the center of the world, and all places are kind of interconnected,” Leary says. “But I think if we live in a particular place, we ought to know about its depth, and its complexity, and its richness over time.” In addition to his time teaching at the UW, Leary has published books and articles, collaborated on documentaries, produced radio programs, curated museum exhibits, worked on folklife festivals, and given talks about Wisconsin’s rich traditions. “That ties in, obviously, with the Wisconsin Idea and the fact that that issue you’re going to be doing work [on is] based on the household traditions of the diverse people in the state,” Leary says. “You have to figure out a way not only to educate students and do your research, but also to return that to the communities themselves.” Here, Leary shares some of that knowledge about the places and practices that hit close to home for many Wisconsin-born-and-bred Badgers:

- Wisconsin has more active varieties of polka music than any other region, and the polka became the state’s official dance in 1991.

Varieties include Bohemian/Czech, Finnish, German, Mexican, Polish, Scandinavian, and Slovenian. Still not convinced this dance runs the state? Governor Tony Evers begs to differ. - Wisconsin’s first record label, Helvetia Records, was founded in Monroe by a Swiss immigrant, Ferdinand Ingold, and featured Swiss American yodelers and accordionists.

In 2018, Leary, along with other collaborators, released a reissue of all 36 recordings that came out of the label, for which Leary received Grammy nominations for Best Album Notes. Leary is currently working with a team of folklorists to develop a free online cache of regional folk music from across Wisconsin. - Rice Lake’s Otto Rindlisbacher — a cheesemaker, sawmill hand, tavern keeper, taxidermist, and renowned proprietor of a Northwoods “museum bar,” The Buckhorn — not only recorded Swiss music for Helvetia, but also recorded Swiss, Norwegian, and lumberjack tunes for folklorists from the Library of Congress.

According to Leary, one of the folklorists who recorded Rindlisbacher was a man named Alan Lomax, who’s “probably the most internationally renowned folk song authority and field recorder” and is often associated with the likes of Lead Belly, Woody Guthrie, and Muddy Waters. - University of Wisconsin researchers Bernice Stewart and Homer Watt published Legends of Paul Bunyan, the first study of the giant lumberjack, in 1916. Later, Franz Rickaby would release Ballads and Songs of the Shanty-Boy (1926) — the first authoritative collection of lumberjack folk songs — which relied heavily on Wisconsin as a source. (The collection was recently reissued as Pinery Boys: Songs and Songcatching in the Lumberjack Era by the University of Wisconsin Press.)

- Eugene Shepard, a former Rhinelander timber cruiser hoping to spark tourism to offset logging’s economic decline, invented the Hodag in the 1890s.

According to Shepard’s 1893 news account of the Hodag (though it notoriously changed with nearly every telling), the creature had “the head of a frog, the grinning face of a giant elephant, thick, short legs set off by huge claws, the back of a dinosaur, and a long tail with spears at the end.” It also bore green eyes, huge fangs, and two horns sprouting from its temples, and reeked of “a combination of buzzard meat and skunk perfume.” - Ole and Lena, stock characters in Upper Midwestern Scandinavian dialect jokes, date back to the 1890s during a surge of working class immigrants from Norway and Sweden.

Lena greeted Ole at the door of their apartment when he came home from work. “Guess vhat,” said Lena. “Remember ve have been talking about getting a more expensive apartment?” “Ya,” said Ole. “Vhat about it?” “Vell,” said Lena, “now ve don't have to look. Da landlord yust raised da rent!” - The internationally-renowned book, The Trickster: A Study in American Indian Mythology (1956) by Paul Riden, is based on a cycle of tales told by Wisconsin’s Ho-Chunk people.

This work also garnered the attention and commentary of legendary psychologist Carl Jung. - Wisconsin’s Friday night fish fry tradition draws on many immigrant, indigenous, and working-class cultural practices.

UW–Madison’s Janet Gilmore, a professor of landscape architecture and folklore and an unofficial expert on the Wisconsin fish fry, recently collaborated on a fish fry–themed opera that played in Madison this past spring. - Wisconsin’s appalling state ghoul, Plainfield’s Ed Gein, who inspired a cycle of grim jokes (Why was Ed Gein expelled from school? He was such a cutup.), influenced Robert Bloch’s novel Psycho and Alfred Hitchcock’s subsequent film, and is the subject of songs by several metal and noise rock bands, including Slayer and Madison’s own Killdozer.

- Eight traditional artists from Wisconsin have received the nation’s highest award, the National Endowment for the Arts Heritage Fellowship.

They are: Louis Bashell (Slovenian polka accordionist), Lila Greengrass Blackdeer (Ho-Chunk maker of black ash baskets and powwow regalia), Betty Pisio Christenson (Ukrainian decorated Easter eggs/pysanky), Gerald Hawpetoss (Menominee moccasin maker), Ethel Kvalheim (Norwegian rosemaler), the Oneida Hymn Singers of Wisconsin, Ron Poast (maker of Norwegian hardanger fiddles), and Sidonka Wadina (Slovak straw artist and folk painter).