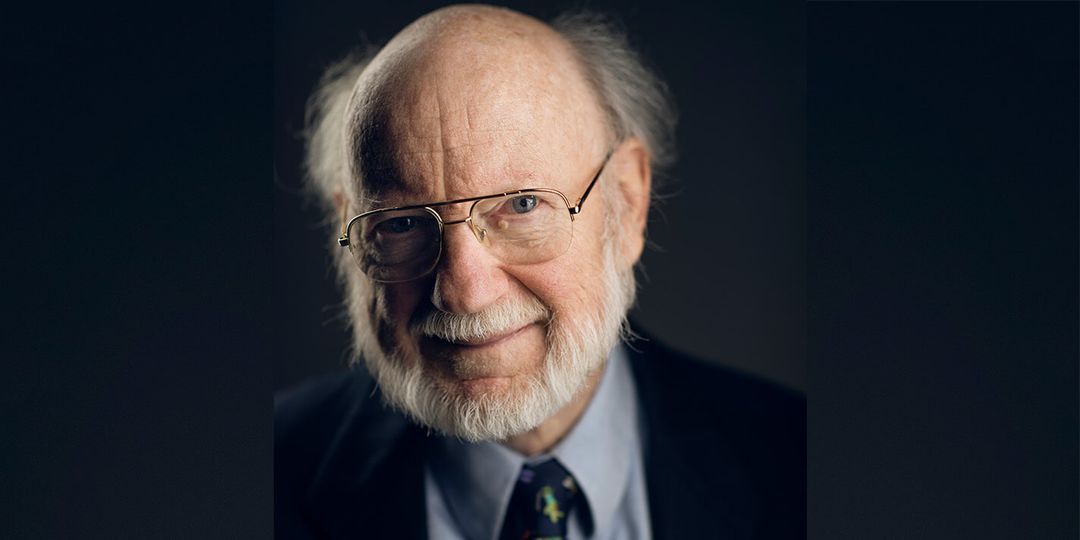

2010 Distinguished Alumni Award Honoree

Out of the destruction of World War II, came Arnold Weiss’s passion to build, beginning an odyssey that has taken him from Jewish orphan in Nazi Germany to retired counsel for a large, international investment-banking firm.

His decorated service in U.S. military intelligence led to his discovery of the final written words of Adolf Hitler, after which Weiss dedicated his 50-year career in international finance to bringing social and economic progress to thousands of people in developing nations all over the world.

Weiss was born in 1924 in Nuremberg, Germany. While a young child, his parents separated and he and his two sisters were left with their mother. Unable to support all three of her children, Weiss’s mother was forced to leave him in the care of a Jewish orphanage in Furth, a suburb of Nuremburg, in 1931.

As the years progressed, the danger posed by the rising Nazi regime became evident. Jewish parents began disappearing into prison camps and the children they were forced to leave behind swelled the orphanage to capacity. As the Jewish community shrank, so too did the funding that the orphanage relied on to operate. Food became scarce and malnutrition rampant, and Weiss also was the subject of regular beatings by members of the Hitler Youth on his daily walk from the orphanage to school.

“You lived from day to day and tried to roll with the punches,” Weiss says. “While generally being a pretty miserable place, the orphanage wasn’t all bad. You always had someone you could play with and talk to. You had companionship. The beatings were unpleasant, but you learned to cope.”

Weiss was fortunate to be selected to emigrate to the United States in 1938 by the Jewish Social Service. Unable to speak a word of English and with nothing but a cardboard suitcase packed with a few clothes, Weiss made the voyage to the U.S. where a foster family was supposed to meet him in Chicago. No one did, and Weiss stowed away on a train to Milwaukee, remembering only that he had heard during his journey that Germans lived there.

Already well-accustomed to institutional life, the 13-year-old Weiss spent many nights in a railway station, which doubled as a soup kitchen during the Depression, an orphanage or a foster home in Milwaukee, before being placed with a foster family in Janesville, Wisconsin.

Finally given the chance for a normal childhood, he flourished. He earned good grades in school and developed close relationships with his foster parents and siblings, the Wexlers, which he has carried with him throughout his life.

“They were just wonderful people,” he says. “I have very fond memories of that time in my life.”

In 1942, Weiss enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Corps, beginning a military career first as an instrument technician and B-17 gunner and ending as an intelligence officer responsible for bringing Nazi war criminals to justice. He arrived in Paris in 1944, before advancing with his division to the Battle of the Bulge. Weiss was also part of the American liberation of the Dachau Concentration Camp, a harrowing experience for the native German that has left an indelible impression in his mind.

“It was hard, yes, but I was in a much better position to take it than most because of my experience in the orphanage,” he says. “You learned to live by your wits. The discipline of the orphanage was in me. I was used to sharing sleeping space with a whole bunch of people and taking instructions.”

Since he was one of the few American soldiers who was fluent in German, Weiss’s main duty became the interrogation of Nazi prisoners, a job that could demand as many as 20 hours per day from the 21-year-old soldier.

After the German surrender, acquiring evidence of Adolf Hitler’s death became an international priority. Arnold and a British officer were summoned by the Allied Supreme Headquarters to lead a group in pursuit of this evidence, and their efforts soon resulted in the capture and arrest of SS general Wilhelm Zander, who had been with Hitler in his bunker just prior to his death.

“There was no immediate indication that this guy had anything of value,” Weiss says. “But when I was interrogating him, he said to me, ‘I suppose you want the documents?’ I said ‘yes’ having no idea what the hell he was talking about.”

Zander led Weiss to a hidden briefcase on his property, and before long, Weiss realized he had discovered the last will and political testament of Adolf Hitler and the marriage certificate of Hitler and Eva Braun.

“I was shocked,” Weiss says. “I couldn’t believe what I was reading.”

Detailing succession plans, the documents eventually became important evidence at the Nuremberg Trials in trying remaining Nazi officials, and Weiss was honored with the Army Commendation Medal for his important discovery.

Weiss stayed in Germany until 1947 as a military intelligence officer working with the U.S. Treasury to trace assets of the Nazi Party, before returning to the United States to attend the University of Wisconsin. With little money and a strong work ethic, Weiss used the four years he had earned through the G.I. Bill to earn undergraduate degrees in political science and economics as well as his law degree.

“I enjoyed law, especially my work with the U.S. Treasury in Europe,” he says. “I became fascinated by it. I also worked as an interpreter and translator for the Nuremburg Trials and law seemed like a great way to earn a living.”

Outside of a constantly full course load, Weiss spent his four years at the university active in politics and the Hoofers Hiking Club, and he was a house fellow in Goldberg House. When he needed to relax, he and the other house fellows would congregate at the Hasty Tasty, a former tavern on University Avenue near Engineering Hall.

“I have always looked back on the university as a very pleasant experience,” Weiss says. “I made a lot of good friends there and my house fellowship was by far the most interesting and rewarding experience.”

Following graduation, Weiss returned to work for the U.S. Treasury as general counsel to the Office of International Finance. Weiss led efforts on behalf of the Treasury to promote international regulatory policy, support financial stability and develop international economic policy engagement and coordination in the recently formed International Monetary Fund and World Bank — both vital sources of financial and technical assistance to developing countries around the world.

Midway through his eight-year tenure at the Treasury, Weiss was introduced to Artemis Lychos through a mutual friend and roommate. They married in 1956 and had two sons, Daniel and Andrew, and Weiss is now the proud grandparent of three grandchildren.

“I was lucky in being married to a very good wife,” Weiss says. “She was very smart. I now try to spend as much time with [my grandchildren] as I can. The two young ones can wreck the house in no time, and the older one, like most teenagers, knows everything.”

When the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) formed in 1959, Weiss was selected as part of the U.S. delegation to help the bank get started.

Headquartered in Washington, D.C., the fledgling organization was in need of the strong leadership and expertise Weiss could provide, but he quickly learned that his duties would cover more than just legal counsel.

“It wasn’t just the legal work that needed to be done,” Weiss laughs. “I did everything, including getting the phones in and the furniture rented and put in place. It was a great experience. I am very proud to have helped create it and eventually we were able to enlarge its membership to non-reachable countries.”

Weiss set to work on building the framework for what has now become the oldest and largest regional multilateral development institution. He drafted the IDB’s charter to govern principal functions and goals for the bank, reaching its mission to finance the development of the borrowing member countries, supplement private investment and provide technical assistance for development plans and projects.

Over his 18 years as general counsel to the bank, Weiss would oversee operations in matters covering economic and social development, including agriculture, industry, energy, transportation, public health, education and urban development.

As his sons approached college, Weiss left the IDB in 1978 for the private sector and became partner at the Washington, D.C. law firm of Arent, Fox, Kintner, Plotkin and Kahn. With his extensive experience and leadership in the IDB, Weiss was a perfect fit to head up the international group, where he handled matters dealing with Latin America.

In 1992, Weiss returned to international finance and assisted in the creation of Emerging Markets Partnership (EMP), an investment-banking house dedicated to making equity investments in infrastructure in developing countries. There, Weiss served as senior vice president, general counsel and secretary.

During his 13-year tenure, he helped grow the organization into the world’s largest private equity firm investing in emerging markets, with seven funds holding $6 billion in cumulative capital commitments. Its investment operations span the globe from Korea to South Africa to Argentina and aid in the creation of agribusiness, power and water, telecommunication, transportation and other industries.

“I think it’s the war that changed me more than anything else,” Weiss says. “I decided I wanted to build rather than destroy. In Belgium, Luxemburg, France, Germany … there was so much destruction. I knew there was a better way of doing things. Going into development work and making a good living doing it proved to be a worthy choice and I’m very proud of what I was able to accomplish.”

A testament to the American dream and the resiliency of the human spirit, Arnold Weiss overcame a childhood filled with disadvantage. Through his leadership, expertise and compassion, he built a legacy of progress to bring social and economic progress to developing nations all over the world.