For Dipesh Navsaria, books belong in children’s medical checkups as surely as growth charts and vaccines. Trained in pediatrics, public health, and library science, Navsaria has spent decades exploring how shared stories shape the earliest stages of development. He works across clinics, classrooms, and policy circles — holding joint appointments at UW–Madison’s School of Medicine and Public Health and the School of Human Ecology — to champion literacy as a family-based public health strategy. Today, he uses those books to spark early brain development and strengthen family bonds from day one.

Support future generations of Badgers with a gift to the WAA Scholarship Fund .

Make a GiftWhy is literacy so important for children’s health and well-being?

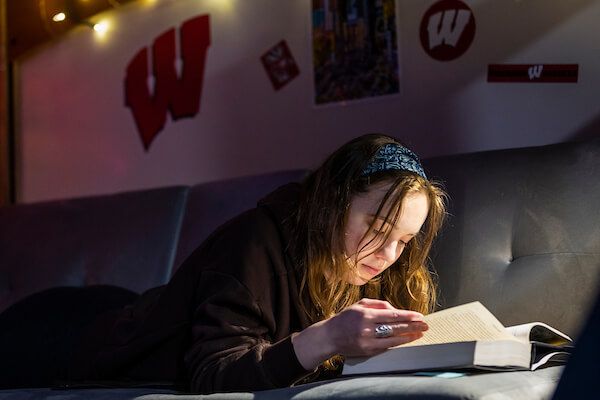

The earlier a child is exposed to books and reading together, the more they learn — how to turn pages, understand that text has meaning, and develop print awareness and early word recognition. But there’s another critical piece: shared reading offers an understandable, approachable way to build early relational health — the health of relationships. Decades of research show strong relational health may be one of the most important factors affecting a child’s life course. By asking, “Do you have an opportunity to share books together?” we open the door to a scaffold that makes relational health understandable. Shared reading becomes a simple, powerful way to build both literacy and connection.

Do educational apps or videos have the same effect?

There is nothing else that causes development to move forward in the first years of life more than interactions with loving, caring adults. Period. There’s no toy, there’s no video, there’s no app that’s going to do that. Evidence shows that when there is a benefit, it’s only when the video’s being co-viewed together with an adult who then talks about it and connects about what they’re seeing. It’s not from a young kid sitting down in front of the video on their own. The kid will watch the video because there’s moving stuff and music and all that sort of stuff. But all that does is attract their attention.

As one of my colleagues, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician, once said when asked about the best toys for a young child: “Parents are the best toys.” And that’s true, because all that fine, nuanced interaction and engagement — the “back-and-forth” and the love — are things no device can bring.

And as someone else once said, “There is no app to replace your lap.” And that’s very true.

What is one piece of advice you have for parents?

I would say, as to the extent possible, talk, read, sing, play with your child. Once you get beyond the obvious basics — feed your child, be with your child — this back-and-forth interaction is incredibly important because it’s what builds that brain. It doesn’t (and realistically can’t) be constant or present every second of the day, but good, high-quality interactions sprinkled throughout the day are what we know works.

What is the mission of Reach Out and Read Wisconsin?

Reach Out and Read Wisconsin integrates early literacy into pediatric care and is the Wisconsin presence for the national Reach Out and Read organization. At every well-child visit from birth to age five, clinicians give families a brand-new, developmentally appropriate, high-quality book and, even more critically, intentional skill-building: reinforcing, guiding, troubleshooting, and supporting daily shared reading at home.

We started 15 years ago with about 55 clinics. Today, we’re in 317 clinics, serving nearly 40 percent of Wisconsin children under age five — with just 10 of our staff but also thousands of clinicians volunteering their time and talent by doing this during checkups. The goal isn’t just handing out books — its helping parents build skills and confidence so reading becomes a daily routine. By promoting shared reading, we strengthen parent-child relationships and support healthy brain development during the most critical years.

How do books help you as a clinician?

Books allow me to do my job better. I walk in with the book in my hand, give it directly to the child, and watch what they do with it as I’m saying my hellos. Does the toddler take the book, study it, and toddle over to their parent and hold it out with that “read to me” gesture? They just told me volumes: “I know what this is. I want you to read it because I enjoy it and I love you.” Or the five-year-old who jumps off the exam table, grabs the book, flips pages, and says, “Oh, I love this book!” In six seconds, I’ve learned about gross motor skills, fine motor skills, language, vision, hearing, and that they’re being read to — without asking a bunch of rote yes/no questions.

Books make my job easier and more meaningful. In a visit with no other concerns, I learn more from giving a book than from my stethoscope. It’s that useful and important. Books are such a great tool to show you so much about kids and their families.

How can parents learn more about literacy, relational health, and more?

There’s an excellent research database and more information at www.reachoutandread.org, but an enjoyable route is our award-winning podcast, now in its sixth season. I’m admittedly biased, since I’m the host and executive producer, but I think we have some really amazing conversations with remarkable people that think deeply about children, families, books, parenting, and health in so many different ways.