Bring me the head of Alice in Dairyland.

I don’t mean to sound ghoulish — I don’t want the braincase of Gena Cooper ’05, the fifty-eighth and (until June 5) current inhabitant of the Alice persona. I’m not after flesh and bone. I’m after legend. I want the head of the Big Alice, the ten-foot-tall mechanical statue that used to stand astride the State Fair like a milkmaid Colossus.

Back in 1948, when Wisconsin was celebrating its centennial, the Alice in Dairyland concept was born out of a fetish for legacy, for connecting the state’s storied past with its ambitious future. That first Alice, Margaret McGuire Blott, hosted the State Fair’s Centennial Exposition. To show that she was more than a pretty face — that she was also a symbol of technological innovation — the fair constructed the ten-foot mechanical Alice.

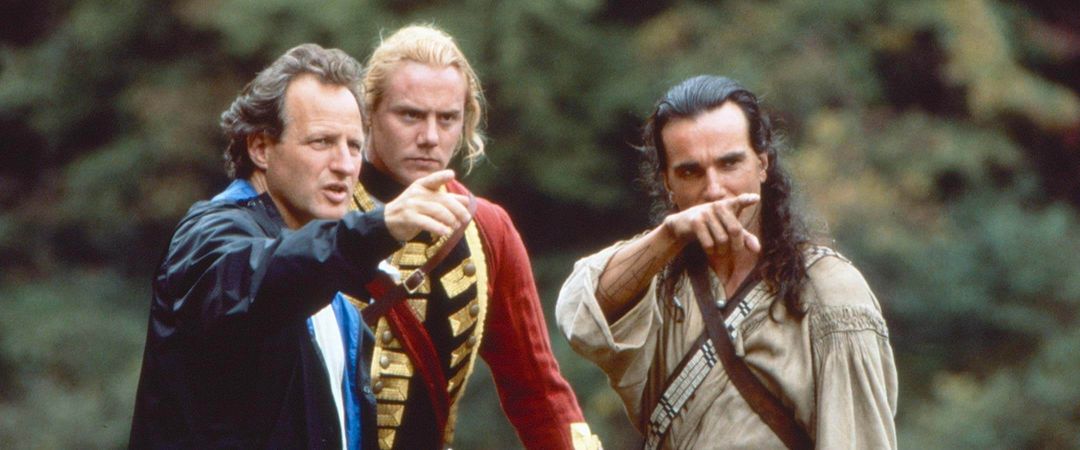

Behind Big Alice was a screen with two-way mirrors1, and hidden behind the screen were Blott and members of her court. They could work levers to make Big Alice stand and sit, and because the robot had a speaker in its mouth, they could make it talk to the crowd.

“Parents loved it,” says Jerry Zimmerman, the fair’s historian. “And kids were — well, maybe awestruck is the best word. It frightened them, I think, but there was a sense of wonderment, too.”

Because Big Alice was a hit with fair-goers, it returned each year. But Blott didn’t — then, as now, Alice was an annual appointment. To make sure that the giant always looked like each year’s reigning woman, the fair took off its head and changed its complexion, hair, and eye color.

That’s the head I want.

Big Alice is gone now, removed from the fair2 after about a decade’s use. And it’s no surprise. A giant android must have seemed like the epitome of futuristic technology in 1948 — the Wizard of Oz brought to life. But today it would look hopelessly quaint.

The human Alice might have met a similar fate, had she not learned to evolve. People such as Gena Cooper have kept Alice relevant by elevating her from an agriculturally themed beauty queen into the symbol for legacy she was meant to be: a marketing force that personifies a unified flow from farming’s traditions to its high-tech future.

As Alice, Cooper3 has spent much of the past year on the road, speaking to elementary and high school classes, media outlets, and commodity groups. When she’s sitting still, however, she’s usually on the fourth floor of the Department of Agriculture and Consumer Protection’s office building on the far east side of Madison, where the only farm in sight is a cubicle farm — a room full of four-foot-high fabric walls.

As a professional setting, it’s one many recent grads would recognize, though Cooper’s salary — $35,000 — is a bit low for someone with a degree in biochemistry. Still, her perks include a greater number of tiaras (one) and sashes4 (ten) than most of her classmates will receive. The tiara — which is made of fourteen-karat gold, platinum, and diamonds and includes three large stones (two citrines and an amethyst) — is actually the third crown the agriculture department has had to commission for Alice. Two previous tiaras were either lost or stolen5 and haven’t been recovered. When Cooper isn’t wearing it, she keeps it locked in a wooden box6.

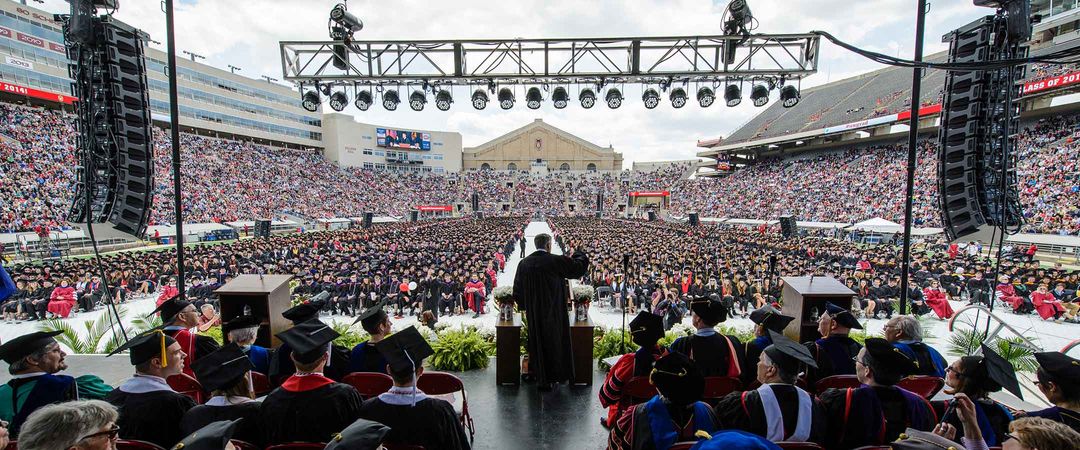

“These are some of our mementos of antiquity,” Cooper says. And the position gives many nods to antiquity. Such as selecting only women. Or announcing each year’s new Alice during a crowning ceremony. Or the fact that, for the entire year that Cooper spends in the job, people will always publicly call her Alice, not Gena. These are relics of that time when beauty pageants seemed the height of shrewd marketing.

The first Alice in Dairyland was selected based on simple criterion — looks. The state’s centennial commission sent out a call for photographs, and of the five hundred submitted, its represen- tatives liked Margaret Blott’s appearance best. Presumably, her milky-white complexion gave visible evidence of the virtues of a diet rich in calcium. The next year, the centennial having ended, the Department of Agriculture took over the Alice program. In the ensuing decades, it used her for a broadening collection of marketing needs. She became not only the face of Wisconsin farming, but its voice as well, making her job more about people skills than an alluring smile.

Today, selecting Alice is far more complex than it was in 1948. Cooper had to submit a resume, write essays, and give speeches, both planned and extemporaneous. This more rigorous process has reduced the number of women who apply for the job down to around two dozen each year. But it helps the state find a candidate who will be able to handle the challenges of being a roving agricultural ambassador.

“The first Alices only talked about cheese7,” Cooper says. “I have to cover the entire agricultural spectrum — not just dairy and corn, but mink farms, fish farms, ginseng growing. It’s a lot to understand and communicate.”

As agriculture has become more diverse, it’s also grown more political. Increasingly, Alice’s duties include answering those who protest farming practices — and not just dairy and fur. At an event promoting the use of ethanol as a fuel, Cooper was physically confronted by an ethanol opponent.

Cooper, who was raised on a farm near Mukwonago8, Wisconsin, feels a keen interest in protecting the Alice legacy. “Alice is a part of Wisconsin’s history,” she says. “She’s a woman that people throughout Wisconsin respect. Having grown up on a farm, I know that female agricultural role models aren’t easy to find. Alice in Dairyland has truly been one of the most visible role models for women in agriculture.”

And so she proudly answers to a name that isn’t hers, faces down activists, promotes milk-drinking among high school students weaned on soda, and responds to inquiries about a ten-foot- tall mechanical statue that disappeared before she was born and that will never bear her likeness.

“It’s what people ask about more than anything else,” she says. “They remember that statue.”

If Jerry Zimmerman has his way, a new generation will be awestruck by Big Alice. He’s looking for a sponsor to finance construction of a replica of the robot. The original, unfortunately, is long gone. Big Alice went into storage when it became too expensive to maintain. Left in a barn, it slowly disintegrated, and no one ever heard of it again.

Except for its head.

“A few years ago, a Milwaukee Journal reporter named Loren Osman said he saw it in a rummage sale going for ten or twenty-five dollars,” Zimmerman says. “Now he kicks himself every day because he didn’t buy it. I guess I would, too.”

A new Big Alice would be something. But it seems to me that, to perfect this monument to legacy, it would need to top that new body with its original noggin. And so, if you know where it is, please: bring me the head of Alice in Dairyland.

This article appeared in the summer 2006 issue of On Wisconsin magazine. Seen any suspicious big, mechanical heads? If so, contact John Allen, On Wisconsin’s associate publisher.