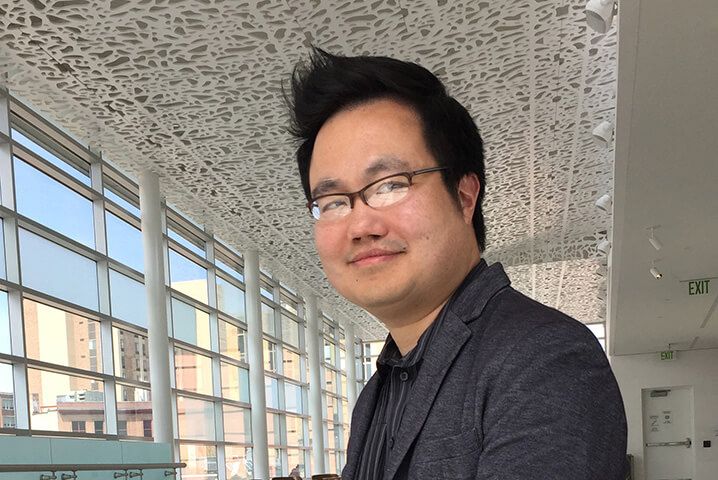

As a third-grade student in Chicago, Timothy Yu lay on a playground slide, staring at the clouds, dissecting their strange shapes. He wrote a five-line poem, and less than a year later, he accepted a statewide award from famed poet Gwendolyn Brooks.

Today, Yu’s poems have evolved from cloud images to politically charged essays and narratives. As a professor of Asian American studies and English literature, Yu says his work pushes against non-Asian writers representing Asians, rather letting Asians speak for themselves.

During his career, Yu has weighed in on events or discussions about Asian American stereotypes and cultural appropriation. His satirical Twitter comments, poetry booklets, articles and group discussions make local and national news. He has been quoted on NPR and published and quoted in the New York Times, Slate, and the New Republic. His work ranges from poetry collections, to thousand-word essays confronting historically problematic narratives, to satirical Facebook posts that start broader conversations about the misrepresentation of Asians in American culture.

“Scholars can think that what we do is in a protected bubble where we’re just doing our intellectual work,” Yu says. “But you know, a lot of the work that we do in Asian American studies, it’s very engaged with political and public issues.”

Satirical Narratives

In 2015, Yu posted on Facebook, “Like every poet, from time to time I write poems of which I am somewhat embarrassed. Once these poems have been rejected a multitude of times, I send them out again under the name of Michael Derrick Hudson of Fort Wayne, Indiana.”

His post was directed at another poet: Michael Derrick Hudson used the pen name Yi-Fen Chou for a work that, in 2015, was selected for the Best American Poetry anthology. After being exposed, Hudson claimed that when his poems were rejected, he used the fake Chinese pen name — a strategy that had been successful multiple times.

“I felt that appropriating [Hudson’s] name amounted to a kind of poetic justice,” Yu told Slate in a September 2015 story.

Two years later, Yu published a poetry collection titled 100 Chinese Silences, which he wrote after hearing a poem from former U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins at a reading at Union South in 2011. Collins read a poem called “Grave,” about sitting by the grave of his two parents.

“He’s got a line in the poem that says something like, ‘My father’s silence was like the 100 different kinds of silence according to the Chinese belief.’”

“And I was like, okay so I’m not an expert on everything Chinese, but that doesn’t sound familiar. … And at the end of the poem [Collins] says, ‘Oh and that thing about the 100 Chinese silences, I just made that up.’ I decided right then and there that I was going to write these 100 Chinese silences that he had made up.”

Over the next six years Yu wrote parodies of famous poems by white writers who used Chinese culture in their stanzas. In a 2017 New Republic article, Yu outlines poets like Ezra Pound and Marianne Moore, who were writing at the turn of the 20th century when Chinese people were being banned from America.

“In short, at the very moment that Chinese people are being excluded from the U.S., Chinese things — poems, philosophy, porcelain — are being celebrated by [white] American poets who write as connoisseurs of China,” Yu wrote. “My new poetry book, 100 Chinese Silences, traces throughout modern American poetry this tradition of celebrating Chinese culture while erasing real, living Chinese people, whether it is Billy Collins admiring the long titles of Chinese poems or Dean Young, [in the March 2016 issue of] the New York Times Magazine, articulating a modern American fantasy: ‘I wish I was an ancient Chinese poet.’”

The Threat of an Education

Sometimes when he wants to start a scholarly discussion about problematic representation in literature, Yu says, people feel threatened. Last year, when the Overture Center for the Arts hosted a touring production of the musical Miss Saigon, Yu suggested a panel discussion about the stereotypical portrayal of Vietnamese women and Asian culture. The play often meets with protests from Asian Americans, and though Yu wasn’t trying to institute a boycott, he wanted to give the audience historical context.

After Yu presented the Overture board with the discussion topics, the panel was cancelled. The board also cut a 1,000-word essay Yu wrote for the program, outlining the history of the play and quoting other Asian American scholars and activists.

“What I learned was that even offering that kind of education can be seen as very threatening and dangerous sometimes,” Yu says. “The essay that I wrote, for example, was fairly direct, but almost everything that I said was quoted from someone else or referring to things that have happened. I wasn’t being like, ‘Miss Saigon is garbage, and this is why.’”

Many of his experiences with scholarship, research, and activism return to the same principle of letting Asians represent themselves.

During a conversation at Union South, the same building where Yu first heard that Billy Collins poem, Yu wondered aloud why Madison art venues claim they want to feature more artists of color, but in the end the majority of representation is still predominantly white.

He cites the example of Cambodian Rock, a new play by Asian American playwright Lauren Yee about a woman facing a Khmer Rouge war criminal after her father fled from Cambodia during the war. The play is now being shown all over the country including in New York, San Diego, and Chicago.

“Why can’t we get something like that on stage here in Madison?” Yu asks. “It speaks to how arts and arts institutions in Madison say that they want to diversify, say that they want to speak to these wider audiences. But when and how they think about doing that is really interesting. It doesn’t necessarily translate to putting works by people of color on stage or having people of color front and center on big productions. We’re still primarily seeing work by white writers that features white actors.”