Take a look at the pictures on the following pages. Glance quickly, and you’ll see attractive images: portrait, landscape, geometric patterns.

Look closer.

Each of the images is produced from something unexpected. The artists — faculty and staff at UW–Madison — are creating their works using unusual materials, building small objects into larger images to convey bigger ideas.

Here, the medium is part of the message. While you can appreciate the work for the picture you see, you’ll get a much richer, much more complicated message when you know what that picture is made of and why.

This isn’t unusual — many artists enrich their work through the material they use. A medium can have power, as Jennifer Angus discovered the first time she put one of her signature creations on display.

“The first show was in a storefront gallery in Toronto,” she says, “and I could hear people outside saying, ‘Well, I see they put up a new wallpaper, but I don’t see the art.’ Then they came in and walked up to the wall, and I literally watched them take a step back because they thought they knew what it was.”

And what was it? Well, you’ll see below. If you look closely.

Examine these pictures carefully. The meanings grow larger as your view gets smaller.

Insect Lady

The Work: Otherworldly

The Artist: Jennifer Angus, Audrey Rothermel Bascom Professor in Human Ecology, Design Studies Department

Angus began her artistic career working in textiles. Her first love was archaeology, but she found her anthropology classes boring, and she was drawn instead to weaving and dying. At first, her work often combined cloth and anthropology, looking at folk textiles. And then, a couple of decades ago, her eye landed on a more intriguing mode of expression: wallpapers, of a special sort.

The Medium: Insects

Working in Japan in the 1990s, Angus connected with the children in her neighborhood over a shared interest in the beauty of insects.

“I was doing research in northern Thailand on tribal minority dress and [came] upon a garment. It’s a shawl that had a fringe in which these beetle wings had been strung,” she says. “I had some of these insects in this studio, and it was an open studio day, and these kids were coming through, as kids do on a weekend, looking for something to do, and they saw the insects.”

The children figured Angus was a bug fan like they were — several of them kept insects as pets. They brought Angus stag beetles and rhino beetles, and when their pet bugs died, they would leave them with her. And Angus began to dress the tiny corpses up in paper kimonos and arrange them in little scenes. Her staging grew increasingly complex, but after she created a dead-insect circus, she felt that she had taken anthropomorphic bugs as far as she could. Still, she couldn’t get the insects’ inherent beauty out of her mind.

“To me, these metallic colors — how can that be possible in nature?” she says. “I was just kind of obsessed, but what I teach is textile design. I’m very invested in pattern and the meaning it can carry. So, I just had that aha moment: I’m going to take the insects and I’m going to put them in patterns.”

The Big Idea

Since then, Angus has been covering walls with desiccated insects in elaborate geometric arrangements. At first glimpse, viewers just see shapes and swirls. A closer look produces cognitive dissonance. “It looks like wallpaper, and wallpaper suggests domesticity, but what’s the one thing we don’t want in the house? Bugs. There’s the tension between what we know and what we fear,” she says. “For about 10 years, I ran with compulsion and repulsion.”

The longer Angus worked with insects, however, the more she wanted to say. Insects are beautiful, and they are important, and she wants viewers to develop a better understanding of insects’ value as living things. Using bug parts for art isn’t new. The Thai cape used wings to add green sparkle; for centuries, artists ground up cochineal insects to create red dye. Angus keeps her bugs whole so that people see the body and not just the color.

“There is a certain reverence and respect for the insect in its whole form,” she says. “When you take it apart, it just becomes a commodity, a piece. These were once living creatures.”

Angus has had her work shown in museums around the country, most notably at the opening of the Smithsonian's Renwick Gallery in 2015. She hopes that her art brings viewers a sense of appreciation. “This has really become the direction of my more recent work,” she says. “Now, one could describe it was catch-22. How do I do this? I’m using real insects to promote the preservation of the insects, and my answer to that is that these are adults. Most adult insects, their lifespan is extremely short. I say that they’re ambassadors for the species.”

Keep It under Your Hat

The Work: Squad

The Artist: Faisal Abdu'Allah, Chazen Family Distinguished Chair in Art, Associate Dean for the Arts, School of Education

A native of London, Abdu’Allah entered school with a simple choice, law or medicine: “That was the path my father said, law or surgeon.” But a field trip to the National Portrait Gallery set him on a different path.

“I walked in, and I just felt like this feels like home,” he says. From that day, he knew that he wanted to be an artist, to create in the same way as the masters he was set to copy: J. M. W. Turner, William Blake, John Constable. But he also saw what those artists and their works missed: people who looked like him, people of color. “One thing stuck with me as I was walking around. I noticed all the paintings that had my body in the paintings, they were either holding a tray or they were being impaled or they were in chains,” he says. “I decided that I would make a contract with myself to ensure that I would always find a way to create a permanent, positive index of my own body or bodies that look like mine for the betterment of myself and younger eyes entering these spaces.”

Squad offers a particular take on Abdu’Allah’s contract with himself: it includes portraits that, in a particular sense, make an index of bodies.

The Medium: Hair

Abdu’Allah works in a wide variety of media, but one is especially personal, not only for him but for his subjects: their hair. Still, you wouldn’t know it at first glance. The hair in his portraits doesn’t look like hair. Abdu’Allah takes clippings from his subjects, freezes them with liquid nitrogen, then crushes them into a powder. Using glue instead of ink with a screen-printing process, he then flocks the powder onto a canvas, and the particles stick, creating portraits. The method, so far as Abdu’Allah knows, is unique. It’s something he invented on the UW–Madison campus and combines the university’s mix of art and science.

“I was a visiting artist; I wasn’t a professor then,” he says. “I just did the investigation here because it’s a research institution, so I utilized all the facilities that were available to me.”

Hair can be political, particularly in a racial context. But it’s also biological — it contains a person’s DNA. In the Squad portraits, Abdu’Allah mixes all the powdered hair together to represent both the subjects’ individuality and their common humanity, and the result is a single, rich color. “It’s kind of auburn,” he says.

The Big Idea

Squad and its hair portraits do more than merge art and science. The project began when Abdu’Allah was visiting with a group of people in Scotland who were preparing to go through gender reassignment surgery. Members of the group referred to themselves as the Squad, and part of their transition was to have their hair cut, which they looked on as a rite of passage.

“They were talking about that shift and what the moment of cutting their hair meant to them, the removal of the old and the bringing of the new,” he says. Abdu’Allah looked at the hair on the floor and figured out how to make it into a usable art medium, to create portraits that would encapsulate the whole of his subjects.

“It dawned on me that we carry the DNA of all of our ancestors through our own hair,” he says. “Our hair has the capacity to always come back in its natural state so we can bleach it, we can straighten it, but given time, hair comes back to its natural state. These images … bring back to life their new identity with their new kind of aesthetic.”

Abdu’Allah has been building up a body of images from his Squad project, growing it beyond the original Scottish subjects and adding more people and more hair: in Madison, he’s done shows in which he cuts the hair of new subjects, which he later pulverizes to make more portraits. He keeps aside a bit of the powdered hair for something in the future. “It’s a way of me holding on to a piece of that person in perpetuity,” he says. “For me, the hair is a really important component for how we identify, a way in which we keep our ancestors alive.”

Unraveled Threads

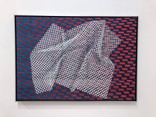

The Work: Gradient Slippage

The Artist: Marianne Fairbanks, associate professor of design studies, in the textile and fashion design major

When she was studying in Michigan and Chicago, Fairbanks was a fiber artist. At the UW, she’s in textile design. “In the art realm it’s called fibers, and in the design realm it’s called textiles,” she says. What’s the difference? “That’s a whole other story.”

The Medium: Woven Fibers

Fairbanks enjoys working with a variety of different kinds of fibers — cotton, wool, and more — but recently, a lot of her work is paper fiber, which she spray-paints into the colors she wants before weaving it into an image.

“Wool or cotton just won’t spray-paint as well,” she says. “The thing that I like about spray-painting these flat yarns is that the color is not super consistent, so I can get a little bit more of a painterly effect. And then also, the color’s quite matte.”

Fairbanks uses a digital Jacquard loom that she acquired for the School of Human Ecology, which enables her to weave elaborate images. The loom can have up to 2,640 different threads going at once. Often, she likes to form patterns that create optical illusions so that viewers will be drawn in to look deeply at her work. “I expand the patterns and expand it and hit you over the head with color in an attempt to get you to look a little longer,” she says. “When it’s so small, we can ignore the intricacies of cloth.”

The Big Idea

One of the important points Fairbanks wants to highlight is that weaving and fibers are a form of technology.

“The writer Elizabeth Wayland Barber who talks about the String Revolution, and how string was one of the first technologies to allow the human race to conquer the earth,” Fairbanks says. “Spinning a thread to become pliant, to have strength, is so amazing, because it allowed us to fish, and create a line that could then be woven and protect our bodies. … We gratefully get to use such things as towels and clothing and stuff, but because they’re so familiar, we ignore the high level of intelligence that went into creating that thing.”

At first glimpse, Gradient Slippage seems to be about very simple technology: it’s a woven image of a rug mat — the grid-like pad that keeps a rug from slipping on the floor — against a colorful bricklike pattern.

“It’s very meta. It’s a weaving about a weaving about a weaving. But I’m trying to unravel all the different ways that the textile is working and show it to you in a new way,” she says. “I was really drawn to the rug pad as this faux textile, or this very modern, fake textile that we rarely even see because it’s under the rug. I’m using different weave structures to show it as an image, while the background is woven with a satin binding. The pattern you see in the background is actually an enlarged view of the satin weave structure itself. It’s the system that you are using to bind the cloth. But the binding itself is giving you so many different levels of information.”

Brick by Brick

The Work: Madison, Lauer Realty Group, 2526 Monroe Street

The Artist: Aaron Williams ’02, Landscape Architect, Division of Facilities Planning and Management

Trained as a landscape architect, Williams is an assistant planner and zoning coordinator with UW–Madison. In other words, he knows buildings. With his art, he’s re-creating sites from around Madison — not architectural treasures, but simple shops from around the city, with a particular fondness for Madison’s murals.

The Medium: Lego

Specifically, white Lego bricks and tiles. (“Tiles are flat,” Williams explains. “Bricks are the ones with studs.”) Williams didn’t come to Lego seeing an opportunity to create art. The first time he used them — as an adult, that is — he looked at them as toys, relics of his childhood. When he sat down to build things, his initial goal was to bond with his seven-year-old twins, Jack and Kate, while the whole family was stuck at home during the pandemic.

“They’ve been playing with Lego since age three or so,” he says of Jack and Kate. “And I had all my Lego from when I was a kid, but I hadn’t touched them for the last 25 years. When I got to 15, I probably quit, whenever it was not cool anymore. My kids are the ones who got me back into it, because we had to spend so much time together when we were quarantined.”

But slowly, Williams started to see Lego as something more.

The Big Idea

Williams began re-creating the structures along lower Monroe Street as a sort of therapy during the pandemic. “I started with wanting to do all of those buildings because those are the places that I would walk by every day that I could no longer go to,” he says. He started with easy buildings — the ones with boxy shapes — and, proud of his creation, posted photos to his Instagram account.

“After I did the Madison mural one down here,” he says, “I got a lot of attention.”

That made Williams think: he could use his pictures to support the shop owners in his neighborhood, people whose livelihoods were at risk due to pandemic closures. “Maybe I can bring some attention to these people with my 120 followers,” he says.

But Williams also wants to say something deeper with his Lego constructions, which is why he sticks with white. “I remember being introduced to the work of Louise Nevelson, who was an artist in New York back in the sixties,” he says. “She would do found objects around the city. She would just pick up things on the curb and then nail them together and then paint them either all white or all black or all gold. Her white ones, to her, represented this emotional promise. And that’s why [my buildings are] white. For promise. For hope. Right now, it seemed appropriate.”

As his buildings have gained attention, the number of Williams’s Instagram followers has grown — to 755 as of press time. And Instagram is just about the only place to see a Williams structure. He only has 25,000 or so white Lego pieces, which may seem like a lot, but it’s only enough to have three or four buildings going at once. Once he’s finished a building and posted its photo, he tears it down so that the bricks and tiles can go to the next project. “My process is really about the act of building and creating something,” he says. “How am I going to make this, replicate it, edit this building that’s got very real texture and form and complexity to it?”

As the pandemic passes, Williams has found less time for building, though “rainy days are much more productive than nice days.” His children long ago stopped wanting to build Lego with him. “To them, this is the weird thing Dad does,” he says. “They’ve moved on with their life, which is great, but I’m hopeful they’ll come to appreciate it down the line.”