Think about the last time you had a headache. Perhaps you ran down the list of reasons it might have come about: Were you dehydrated? Did you sleep funny the night before? Knock your noggin? Stare at a screen for too long? Might you need glasses? Could it have been stress? Something more serious? Did you just need a snack?

While it may be no great feat of medicine to posit diagnoses for a benign headache, the list of possibilities that our minds can quickly conjure speaks volumes about the infinite complexities and elusive quality of anything that falls under the umbrella of “health.”

Humans have been exploring health for nearly as long as we’ve existed. While we’ve come a long way from prehistoric healing practices and the days of the first documented physicians of ancient Egypt, there’s still a lot we don’t fully understand. The more we learn about our health and well-being, the

more questions we uncover.

Nowhere is this truer than at UW–Madison. A Badger's essence lies in seeking unanswered questions and relentlessly sifting and winnowing for their solutions, and the UW's steadfast dedication to the shared human task of bettering health and well-being aligns with the Wisconsin Idea’s commitment to serving those beyond the bounds of the classroom.

UW–Madison confers professional degrees in medicine, pharmacy, physician assistant studies, physical and occupational therapy, social work, nursing, public health, and veterinary medicine, to name just a few, and it offers interdisciplinary research opportunities in all these areas of scholarship. Any attempt to comprehensively document all the ways in which the UW is forging the future of health and wellness would require tomes that would intimidate even the most diligent medical student, so here we highlight just a few.

It's ’Bot Time

The Ion bronchoscopic robot puts the "in" in insight.

By John Allen

No one wants lung cancer, but if there’s a chance you might have it, you could hardly be in better care than the robotically extended hands of Andrea Axtell.

Axtell, a thoracic surgeon, joined the staff at the UW’s Department of Surgery in September, and like most UW doctors, she’s dedicated to the ideal of helping people get well. Cancer surgery is her passion.

“The first day that I walked into an operating room, I knew that this was what I wanted to do,” she says. “I really love the care of cancer patients. I love that you have a longitudinal relationship with somebody. You’re getting these patients through one of the worst times in their life and have the opportunity to help them achieve long-term survival.”

Axtell is passionate, but that’s not what makes her cool. What makes her cool is the robot.

Axtell did her residency at Massachusetts General Hospital. There, she became familiar with the Ion device, a robotically assisted bronchoscope. A bronchoscope is a tool that enables a doctor to look (scope) inside a patient’s lung passages (bronchi), seeking evidence of disease (such as nodules that might indicate the presence of cancer).

The Ion is superior to earlier bronchoscopes in that it’s smaller — the tube that carries the camera inside

the patient is only 3.5 millimeters in diameter, as opposed to a traditional scope’s 4.4 millimeters. If this doesn’t sound like a lot, that’s only because you don’t have a tube jammed into your lung; if you did, you’d realize that every fraction of a millimeter is important. A smaller tube hurts less, and it’s also capable of navigating its way inside smaller bronchial branches.

“You can drive way out into the periphery of the lung,” Axtell says, “to visualize much smaller bronchi that we couldn’t visualize before.”

But the Ion is more than a small tube. Its camera gets information from a CT-scan-generated, detailed map of the patient’s lung, which correlates with real-time imaging. “Essentially you get this GPS map of the entire airway in the lung,” she says, “and it gives you a roadmap out to where this tiny peripheral nodule is, and you can navigate out there, and then you have the option to do whatever you need to do.”

Whatever you need to do could include taking a biopsy, marking a spot with dye, or conducting an ultrasound, all of which enable surgeons like Axtell to perform minimally invasive procedures faster than ever before and with less suffering for the patient.

But more important, the Ion’s speedier procedures give UW Health increased capacity for screening and faster diagnosis, which should lead to helping patients live longer.

“Screening leads to earlier detection leads to increased survival,” says Axtell.

Nursing's Big Four

The UW School of Nursing became a leader in teaching and research thanks to its pioneering deans.

By John Allen

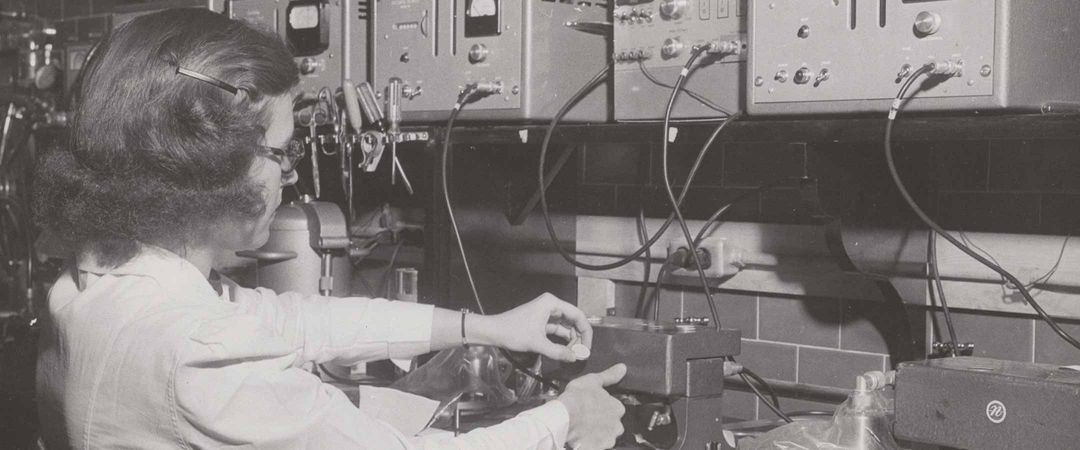

Patricia Lasky MS’68, PhD’80 knows the UW’s School of Nursing inside and out. After arriving in Madison as a graduate student in the 1960s, she stayed and joined the faculty, helping the program grow and develop over the course of 35 years. A professor emerita since 2003, she continues to serve on the board of visitors.

The School of Nursing turns 100 years old this year, and Lasky has been a firsthand witness to more than half its history. When she lists its important moments, you can trust her. The school, she says, has “been significant in providing a workforce for the state of Wisconsin, both for the traditional staff nurse or bedside nurse or community nurse role through the years, and then, parallel with that, being the premier university to develop nursing research for the field.”

In the approach to the school’s centennial, Lasky listed out the names of those who would appear on a Badger nursing Mount Rushmore — the people who lifted the school to a dominant position within the Wisconsin health care community.

Helen Denne Schulte: Though the Universities of Wisconsin Board of Regents authorized creation of a School of Nursing in 1920, it didn’t provide funding for another four years. The school was one of the nation’s first university-based nursing-education programs, as opposed to vocational training offered by hospitals, and the UW hired Schulte to serve as director to ensure that the students received a well-rounded education. Most of the school’s students received a certificate in nursing and a bachelor of science in hygiene.

Helen Bunge ’28: In 1950, the school created a bachelor’s degree in nursing science, and nine years later, it hired Bunge as dean. She oversaw several expansions, including the first male students in 1960 and the first graduate students in 1964.

Valencia Prock: In 1970, Prock became dean, and she elevated graduate instruction further. “When I came to campus in 1965, the school was just starting the first master’s program in the state,” Lasky says. “And when I got my master’s, I joined the faculty, which was the norm for nursing at the time. Dean Prock realized that the nursing school needed to have a research program — a doctoral program — and so she transitioned the faculty from being master’s prepared

to being doctoral prepared.”

Vivian Littlefield: In 1984, Littlefield succeeded Prock and elevated nursing graduate education further. “Dean Prock thought that the faculty had to be part of the biological sciences,” says Lasky. “Well, the biological sciences are bench researchers, a very different kind of research than nursing, which is practice-based. Dean Littlefield basically opened a new world of faculty research based in psychology and social sciences. During her deanship, the school blossomed and realized the dream

of a doctoral program in nursing.”

It's a Small, Small World

In the Tiny Earth Project, students investigate small plots to find the next big antibiotic.

By John Allen

Jo Handelsman PhD’84 has big ambitions. Or maybe small ones.

Handelsman, a plant pathologist who directs the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery, knows that one of the greatest risks facing health care today is the danger of drug-resistant infections.

“We have this rising antibiotic resistance in clinically important populations of bacteria, making diseases — particularly in hospitals, but under lots of conditions — much harder to treat,” says Handelsman. “And that’s coupled with the fact that in the 1980s, the pharmaceutical industry, almost as a whole, pulled completely out of antibiotic discovery.”

Handelsman decided that if she couldn’t convince drug companies to look for new antibiotics, she would try to convince everyone else — or if not everyone, at least thousands of students all around the globe. These citizen scientists wouldn’t need electron microscopes or mass spectrometers. They just needed enthusiasm, a square of soil beneath their feet, and a simple classroom laboratory.

This was the beginning of the Tiny Earth network.

In 2012, Handelsman taught the first course that became the model for Tiny Earth, a program that trains undergraduates across the world to gather soil samples, test them for compounds that inhibit the growth of bacteria, and then forward promising ideas back to lab staff. The course is taught at the UW, and Handelsman’s team — headed by Sarah Miller ’92, MS’98 — trains science instructors at other colleges to train their own students. Now there are more than 16,000 students participating in the Tiny Earth course each year, led by 800 instructors in schools, colleges, and community colleges in 47 states

and 30 countries.

The group in Tiny Earth headquarters at the Wisconsin Institute for Discovery has collected thousands of bacterial samples for further investigation. The next important antibiotic may still be years off, but when

it comes to fighting infection, the future is below our feet.

Mind Over Media

Navigating social media can be like wandering through the wilderness. Experts are keeping kids from getting lost.

By Esther Seidlitz

Social media allows people to learn new life hacks and read the news with a swipe of a finger. You can effortlessly stay in contact with your family and friends, no matter how far apart you live. Users can celebrate their successes — even make a living — by curating picture-perfect public images.

On the flipside, social media also allows imprudent, potentially dangerous trends to go viral. That same easy connection to your friends also gives a bully ceaseless access to classmates beyond school grounds. And with every filtered post online, users are inundated with unrealistic standards about how they should look or act.

Social media is a tool designed with the promise of improving communication and increasing human connection. Depending on how people use such a tool, their online behavior can result in good or bad mental health outcomes.

As interim chair of the UW’s Department of Pediatrics and co-medical director of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) National Center of Excellence on Social Media and Youth Mental Health, Megan Moreno MS’04 has a particular interest in how the good and bad of social media affect teens. Because adolescents are some of the most prolific and flexible users of social media platforms, they’re a valuable resource for researchers working to develop guidelines that promote healthy habits online and protect users’ mental health.

“Teens are in a period of incredible development cognitively and emotionally, and most teens change their social media use patterns as they grow and learn,” Moreno says. “So, even if [they're] in an unhealthy pattern at one point, they are likely to continue to grow and develop and change behaviors into the next phase.”

What does an unhealthy pattern look like?

Just like overconsumption of any medium — video games, television, texting — too much time spent on social media apps comes at the cost of other important opportunities: face-to-face interactions, family dinners, a good night’s sleep. It also increases a user’s chance of exposure to social media’s pitfalls: misinformation, cyberbullying, violent content, or worse.

Adolescents aren’t the only people susceptible to the negative side-effects of too much screen time. “Platforms are designed to engage and reengage users,” Moreno says. “So even adults are subject

to the endless scroll temptation.”

According to Moreno, both teens and adults should prioritize self-regulation and balance. “Healthy media use means learning new things, connecting with new and old friends, having the capacity to create and consume content of interest, and being able to step away from the platforms and enjoy life on and offline,” she says. “I think those things apply to all ages.”

Family media plans can help keep the whole household accountable and engaged in the things that matter. “Parents can help their children navigate social media experience by providing boundaries on time and content, and the AAP’s Family Media Use Plan can help with this,” Moreno says. “Setting boundaries can help teens learn to self-regulate and be present for times when being present is important.”

Moreno stresses that nearly everyone is likely to have a negative experience online at some point. But supportive family members and friends and meaningful, offline experiences can help teens — and adults — build resilience and strike a healthy balance between the digital and physical realms.

The Crossroads of Culture and Care

The Native American Center for Health Professions is enriching Wisconsin’s wellness workforce.

By Megan Provost ’20

When students are admitted to the UW’s School of Medicine and Public Health (SMPH), they participate in a white coat ceremony to mark the beginning of a rigorous educational journey. Upon graduation, some of these students receive a second garment — one with more color and a meaning all its own.

Bright, patterned blankets — traditional gifts that honor an individual’s contributions to their community — are presented to graduates of the Native American Center for Health Professions (NACHP), a hub for Indigenous students pursuing careers in the health professions. NACHP works with students at all points in their schooling — from curious middle schoolers to medical students on the brink of residency — to support the pursuit of their chosen career through mentorship and community-building.

“NACHP is often why a lot of [Native] students choose UW–Madison for their health professional program,” says Melissa Metoxen ’04, MS’07, a member of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin and assistant director of NACHP.

The program’s impact is both abundantly clear and continuously necessary. When Erik Brodt, a former UW Health physician, founded the center in 2012, there were only five Indigenous students and faculty in SMPH. Within its first 10 years, NACHP saw the number of Indigenous medical school applicants and matriculants increase by 300 percent. Today, there are 46 Indigenous students in SMPH and more than 50 across the university’s health professional programs. Over the past decade, NACHP has graduated 91 health care providers and established SMPH among the top 10 medical schools in the country for graduating Indigenous students.

For NACHP graduates, their blankets celebrate not only the care they will go on to provide but also the fact of their presence in health professions. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, in 2020, health care providers who identified as American Indian or Alaska Native made up only 0.4 percent of Wisconsin physicians. In 2023, that number is even lower in a state in which American Indian and Alaska Native people account for 2.5 percent of the population. This disparity is dangerous for Wisconsin’s Indigenous peoples, as patients are more likely to disclose symptoms, experiences, and other relevant information to providers with whom they feel a likeness or connection. As Wisconsin’s population of Indigenous providers dips, NACHP’s work is more crucial than ever.

Metoxen recalls reviewing a physician assistant school application that recounted a memorable experience the applicant had while working in a clinic. The student saw a patient who was also Indigenous and who disclosed new and pertinent medical information [because of] the comfort and trust they felt simply based on their shared life experiences.

“That applicant isn’t even formally trained yet,” Metoxen says. “Imagine [having] a provider that’s an MD that is able to do the same thing.”

Trust Your Gut

Understanding the gut microbiome could solve some of health care’s biggest problems.

By Hayden Lamphere

Imagine having the ability to pinpoint the cause of a disease, design a targeted treatment for it, and possibly eradicate it from the body entirely.

That’s the goal of researchers like Federico Rey, a microbiologist and associate professor of bacteriology at UW–Madison. Rey studies how variations in the gut microbiome impact one’s susceptibility to disease.

Our intestines contain trillions of microbes that interact with everything we ingest, including food, medication, and environmental exposures. “Microbes are great chemists; they break down anything that reaches the gut. The compounds they make from our food and other chemicals enter our body and reach virtually every organ,” says Rey. “We now know that what happens within the gut affects many

aspects of our health.”

His work is part of a relatively new field of microbiology that focuses on finding new ways to combat complex diseases by studying their relationship to the microbes that inhabit microbiomes throughout the body.

Although researchers have previously studied the intestines, the microbes within them have been largely ignored. “There are thousands of processes that microbes can do. The molecules they make affect behavior, vascular health, metabolism, responses to drugs, virtually every physiological process,” Rey says. “Paying attention to the microbiome has changed how we do science in the medical field.”

Now, scientists are finding intricate networks, or axes, between major organs and the gut that are proven to lead to common conditions including diabetes, heart disease, and depression. Genetics, age, and diet all impact the collection of microbes in a person’s gut. By tracking an individual’s unique composition, interventions could be made to understand why a disease is present and potentially find treatments that target it without negatively affecting the rest of the body. Despite the exciting potential applications of this research, many of its breakthroughs are still to come.

“[For] half of the genes that are in the gut microbiome, we don't know what they are or what they do,” says Rey. “We’re still trying to uncover all that.”

Researchers hope that understanding the specific pathways between the gut and the rest of the body will one day allow for detection, targeted treatment, and eventually prevention of major diseases, including diabetes, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s.

“Every institution has a major microbiome portfolio that wasn’t there 10 years ago,” Rey says. “Solutions are coming.”