In the 2002 movie Spider-Man, Peter Parker returns home from his fateful encounter with a radioactive spider when Uncle Ben and Aunt May offer him dinner. “No thanks,” he says. “I had a bite.” Hats off to David Koepp x’84 for the clever line.

Koepp’s screenwriting résumé boasts an impressive collection of Hollywood classics. He’s penned unforgettable scripts for films including Jurassic Park (“Dinosaurs eat man; woman inherits the earth,”); Mission: Impossible (“Relax, Luther; it’s much worse than you think,”); and Indiana Jones (“You want to be a good archaeologist, you’ve got to get out of the library!”).

But before he made it in Hollywood, Koepp was a lifelong lover of movies who hoped to forge a future in film. Growing up in Pewaukee, Wisconsin, he developed his cinematic tastes through the Sherlock Holmes and Godzilla movies on late-night television and the glamorous Old Hollywood films favored by his mother.

“It was so stylish,” he says of Hitchcock’s Notorious, a favorite. “The camera work was fantastic. The romantic tension in it was great. Everything about it was just amazing.”

Like many filmmakers of his generation, Koepp was also captivated by the early work of director Steven Spielberg. He was only 13 when Jaws struck oceanic terror into the hearts of even Midwestern moviegoers, and films like Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and E.T. fueled his fascination with the art of filmmaking.

Koepp was an aspiring actor when he landed at the UW, where he studied under legendary film and theater professors Tino Balio and Ed Amor and read the “late, great” David Bordwell, who later became a close friend. It was also at the UW that he discovered he was better suited to writing for the camera than to acting in front of it.

Today, Koepp writes scripts for intimate, Hitchcockian suspense thrillers and action-packed adventures alike. He’s worked with stars of every generation. He’s written two novels and adapted one to the screen, the pandemic thriller Cold Storage, out next year. And Spielberg, one of Koepp’s early artistic influences, is now a colleague.

To quote Jurassic Park’s Dr. Ian Malcolm, “Life finds a way.”

Why is screenwriting the best role for you?

You don’t need anyone’s permission to write. I don’t have to be hired. I can go home and make it up. I might not get paid for it, but I have that freedom. I also think people that have the writing bug in them recognize that the world’s imperfect and out of our control, so we want to have some area where it’s completely in our control.

You once told David Bordwell that “the world is too big for a movie.” How does this shape your writing?

I find it liberating. If you can say to yourself, “This whole story takes place in 24 hours,” or, “This is all in the house,” those kinds of aesthetic limitations actually widen your thoughts, because now you’re forced to come up with creative solutions. You certainly can write a large, globetrotting adventure that takes place over decades. To me, it’s just really daunting because there are no limits. Anything is possible. That actually inhibits me from writing because I think, “Well, if anything is possible, whatever I write is not good enough.” But if I start at least with some form of container, then I feel like I can get my arms around that.

What makes a movie great?

I think that Spielberg said once that when a movie is great and lot of people love it, it’s not because one person did their job extremely well or was brilliant. It’s because six or seven people were at the peak of their game. Take E.T., one of the most beloved movies ever. That’s Steven at the peak of his game, but it’s also Melissa Mathison writing the best script she’d ever write and John Williams creating a score that you’ll never, ever forget. Jurassic Park works so well as a movie because Michael Crichton, at the peak of his inventiveness, had a genius, once-in-a-lifetime idea. I think I wrote a snazzy script. Jeff Goldblum and Laura Dern and Sam Neill are fantastic. John Williams wrote a fantastic score again, and then Denis Murin, who is the effects wizard who really invented CGI, invented it for that movie, as well as Stan Winston doing some of the best robotics in history.

Are there any behind-the-scenes moments that have been especially memorable?

On Jurassic Park: The Lost World, we were supposed to shoot a scene [in which] a boat runs up on the beach, the door flops down, and the team gets off. The day came to shoot it, and the waves were way too high. We couldn’t land the boat on the beach. I said, “We’re going to go up this river, and there’s all these overhanging trees, and they’re all going to whiz by and it’s going to be jungly and exciting.” We’re roaring up the river, and the boat gets stuck on a sandbar because it’s low tide. “How long until we get off this sandbar?” “Six hours.” All right, let’s rewrite the scene. So, the scene in the movie starts with someone saying, “Why are we stopping?” I had to make up a thing: the captain doesn’t want to go any further because he’s heard horrible stories about what lies ahead. We just rewrote the scene on this boat that’s stuck in a sandbar, and it’s a good scene. It’s just not at all what we intended.

In the first Mission: Impossible movie, Ethan Hunt’s parents live in Middleton, Wisconsin, and the most recent film reveals that he was born in Madison. Was that your doing?

Damn right. Yes. And his parents are named Donald and Margaret, which are my parents’ names. I’m always trying to sneak Wisconsin in there.

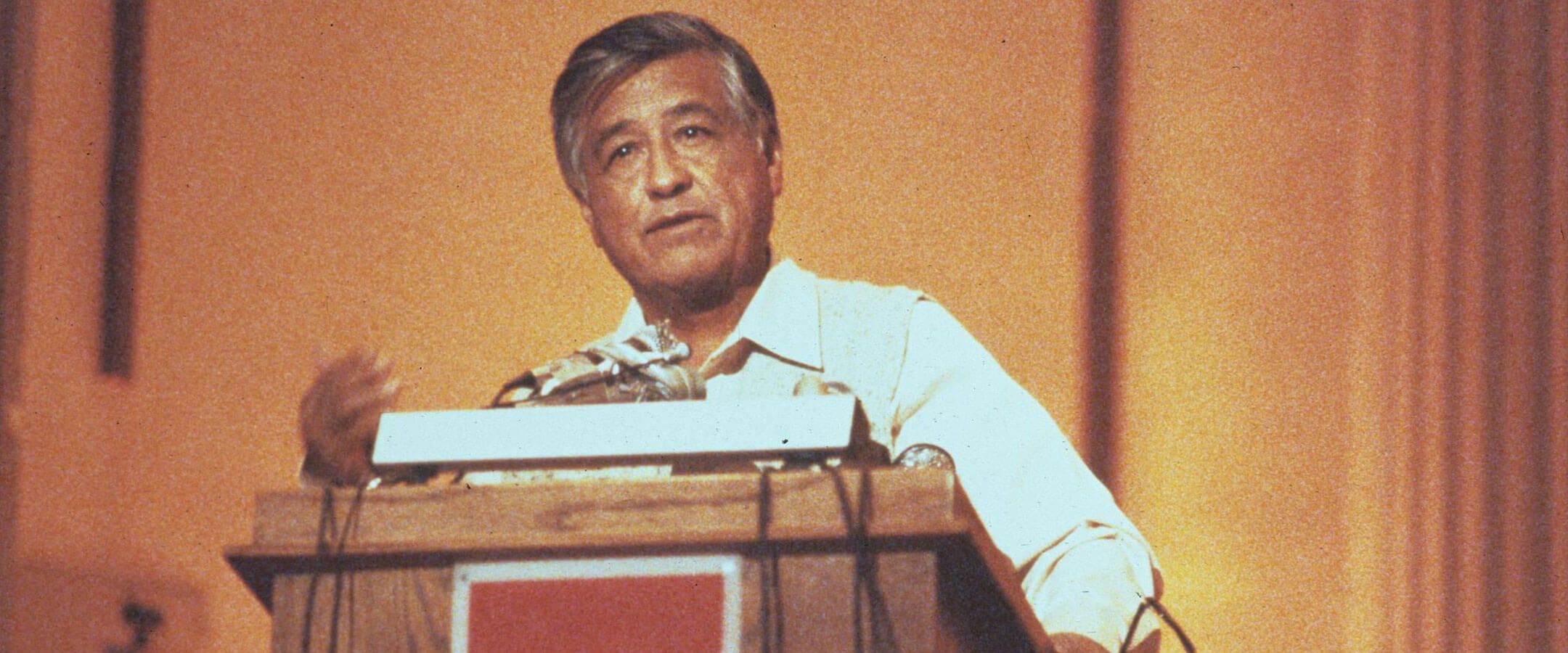

David Koepp (left) converses with director Steven Spielberg on the set of The Lost World: Jurassic Park in 1997. / Getty Images