Freezing rain peppers the oversized windows of room 1310 in Sterling Hall as nearly two hundred bundled-up students hustle in. To the soundtrack of Jenny Higgins’s playlist — Diana Ross, Queen Latifah, The Beatles — they flip open laptops and notebooks in preparation for Monday morning’s lecture. Higgins is a public-health scientist conducting NIH-funded research on women’s health disparities, and this is the famed and perpetually wait-listed forty-year-old Women and Their Bodies in Health and Disease course — GWS 103 for short. Today’s lecture topic is mental health.

“Pull out your iClickers, please. ‘Have you ever been diagnosed with a mental illness or attention issue, including ADHD?’ I’ll give you thirty-five seconds,” says Higgins, and the numbers on the overhead projection screen whirl and climb, flurrying into focus.

Anonymously, each student presses a button on her own small, white remote control. Thirty-six percent answer yes. When Higgins follows up asking if they’ve ever taken prescription medicine for a mental illness, 26 percent click that they have.

“So the overwhelming majority of you who’ve received a diagnosis are taking psychotropic medicine for this, and I want to very carefully honor the experiences of folks who have received these diagnoses,” says Higgins. “But I also want to push back just a little bit. I want us to think about, what does this represent for us culturally?”

During the next fifty minutes, Higgins runs through mental-health data and medical research, viewed through the lens of historical movements, social constructs, and feminist approaches. For example, in North America, she says, 60 to 75 percent of mental-health service clients are women. Women are two to three times more likely to be diagnosed with depressive disorders. But what if we’re actually “pathologizing the legitimate emotional distress” that marginalized groups experience due to systemic inequities? Do postpartum women experience exaggerated rates of chemical imbalances? Does gender inequality in parenting also contribute to depression?

“To have better mental health,” Higgins concludes the lecture, referencing a quotation on the overhead projector, “women need to have more control and power over their lives.”

Students of UW-Madison’s Department of Gender and Women’s Studies (GWS) have been analyzing questions such as these throughout the program’s storied, forty-year history — a milestone anniversary that the department marked in 2015. But what these students may or may not realize is just how rare this class — and the department itself — is. GWS 103 is the oldest and largest course of its kind in the country, and it’s the only natural-science credit course within the department. GWS boasts one of, if not the strongest, science and health core components of any in the country. And it always has.

“Most women's studies programs at the time were focused on the humanities and the social sciences. Very few of them had scientists,” says Judy Leavitt, who came on board in 1975 to teach Biology and Psychology of Women, an upper-level science course, alongside psychologist Marjorie Klein. It was an offering that predated the fledgling women’s studies program and eventually became one of its first three core courses, along with Women’s Studies 101 and Women in the Arts, taught by Susan Stanford Friedman PhD’73 and Evelyn Torton Beck PhD’69, respectively.

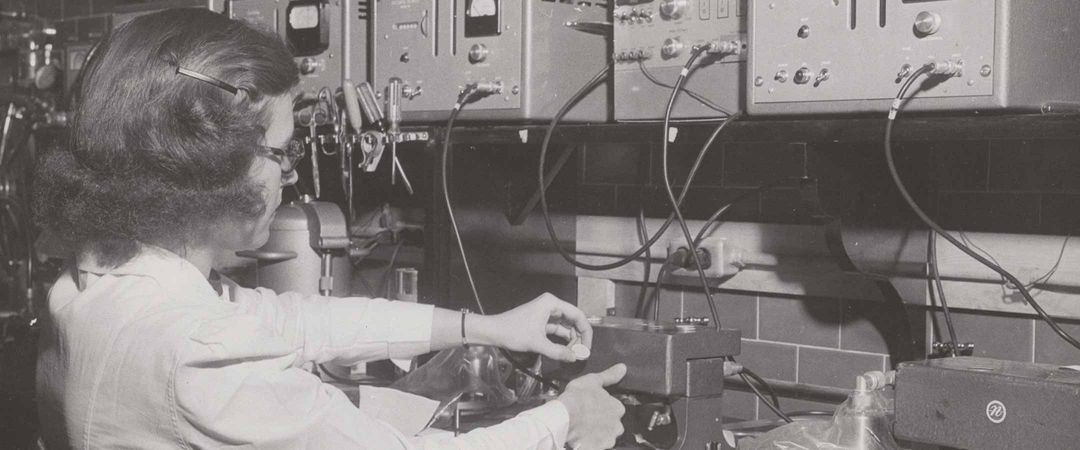

GWS 103 came along shortly thereafter, when the late Ruth Bleier insisted on an introductory-level, science-based women’s studies course. Bleier was a tenured neuroanatomist in the School of Medicine and Public Health and a cofounder of the Association of Faculty Women. She’s also credited with winning equity salary raises for faculty women and staging a “shower-in” protest, which resulted in the first women’s locker rooms on campus.

The interdisciplinary foundation of the program as it was then wasn’t just for the benefit of women’s studies students. Bleier and her fellow pioneers — including Mariamne Whatley, then a postdoctoral fellow in plant biology who taught the first GWS 103 — hoped to influence every department throughout the university. A trained bench scientist, Whatley went on to teach several upper-level science courses within the program, including The Biology and Psychology of Women; Childbirth in the United States; Women, Sex Hormones, and Health; and LGBTI Health.

“We really saw what we were doing as transformative of knowledge,” says Leavitt. “It was part of a larger political movement, but it started with the idea that many of us experienced, and I certainly experienced: that I hadn’t had a single woman faculty member when I was a graduate student, nor had I studied a single thing about women. It was as if the world was male.”

That larger political movement also “came out of a spirit of change that was sweeping the whole university,” says Friedman, who is now a Hilldale Professor and director of the UW’s Institute for Research in the Humanities. “There was tremendous interest on the part of students in rethinking what universities are for, how we change the curriculum to keep up with new ideas, new fields, new ways of thinking.”

When the UW System Board of Regents mandated that all of the UW System campuses teach women’s studies in 1973, Friedman served as a staff associate on the committee that eventually designed UW-Madison’s program.

“Many of these new fields were interdisciplinary, and women’s studies is definitely interdisciplinary,” says Friedman, laughing as she recalls the time that she and her colleagues chose the topic of menstruation to demonstrate the importance of integrating multiple modes of knowledge — biology, psychology, anthropology, sociology, literature, art — to “very embarrassed” members of the board of regents, who’d asked why interdisciplinarity was important to women’s studies.

The story is funny now, but back then the women faced skepticism and hostility throughout campus. Friedman vividly recalls that when Bleier, a respected physician, first proposed GWS 103, it was rejected by the biological sciences divisional committee who said the description “looked like something that would go on a Tampax box.”

“In the beginning, it was extremely risky to be involved with this,” says Friedman. “To establish a whole new field that none of us had any training in, but feeling that it was so important. There was a tremendous prejudice, ignorance, fear about what it was we were doing. Life was pretty tough in the beginning years for all of us in our tenure home departments.”

But GWS 103, like the rest of the department, has proven to be a wildly successful experiment. From the start, it’s had 350 students each semester and another 300 on the waiting list. What’s more, Whatley — famously, every semester, year after year — receives a standing ovation from students after the first day’s lecture.

“The faculty who were so doubted at the beginning have won many, many awards,” says Friedman. “We’ve seen a lot of success, and I think that we feel respected on campus. But I don’t know if we would have survived if we didn’t have the women’s studies community — to give us the strength to go back to our departments and convince them that the research we did was legitimate, that we were rigorous teachers — that we were not running consciousness-raising groups, that we were not just didactic political people, that we were engaged in research just like they were.”

“At a fortieth anniversary, it’s very easy to be nostalgic for the good old days. Women’s studies did some radical things early on,” says Judy Houck MA’84, PhD’98, current chair of the Department of Gender and Women’s Studies. The name change — adding Gender — came about in 2008 when the women’s studies program became a department. The added word is both a reverent nod to the pioneering history and the still-relevant need to center women as a marginalized community, and a modernized reflection of the rapidly evolving scientific understanding of gender.

Today, fourteen faculty members teach twenty-eight undergraduate classes to around one hundred majors and two hundred and fifty certificate students, not including the one hundred cross-listed courses. Last year the department graduated forty-five majors, seventy-five GWS certificates, and twenty-two LGBT certificates.

“These are still thriving research areas, and our students still demand these courses. We are still doing field-changing work when you add a feminist lens to biological questions,” says Houck. “We are trying to hold on to something from our past as we go forward. But other ways that we’re moving forward are brand new.”

Today’s department has evolved to reflect and analyze a changing world. It is developing a new disability-studies curriculum, including Ellen Samuels’s work on the intersectionality of race and disability. Nonbinary [?] gender and transgender experiences are arguably the biggest shift in recent years, permeating departmental courses at all levels.

And science continues to play a foundational role. Just last year the department launched the new Witting Postdoctoral Fellows Program in Feminist Biology, a two-year endowment encouraging a biologist to utilize feminist perspectives.

“If women are better informed about their bodies, they should have better health outcomes,” says professor of psychology Janet Shibley Hyde, director of the Center for Research on Gender and Women, who’s currently pioneering research on gender differences — with surprising results.

“My work over the last ten or fifteen years has shown that males and females are actually much more similar than they are different,” says Hyde, offering the example of math performance. One of her recent studies showed that second- through eleventh-grade public school girls performed as well as boys. “And if you look at bachelor’s degrees in mathematics today, 48 percent of them are going to women.” But when Hyde asks her students to estimate that percentage, most guess between 15 and 20 percent. The stereotype that men are better than women at math and science is a self-perpetuating one, keeping girls from taking these classes in the first place.

“At a fortieth anniversary, it’s very easy to be nostalgic for the good old days. Women’s studies did some radical things early on.”

Moreover, according to Higgins, the fact that GWS 103 counts as a science credit is a big draw for students who are avoiding, say, organic chemistry.

“There’s still a lot of science-phobia among our young women students — this notion of, ‘Yeah, I’m bad at science,’” says Higgins. Capturing them at the 100-level not only dispels that myth, but it also gives them a greater understanding of where that line of thinking came about in the first place.

“The way we think of the world, the way we think about bodies, about health, is culturally constructed,” says Higgins. “What we’re trying to get students to increasingly recognize is that all bodies have social influences placed upon them.”

At the end of each semester, Higgins asks her students to reflect back to the first day of class when they each wrote down learning goals. The iClickers come back out when she asks if they were successful — and the answers are positive. As for her goals, Higgins hopes that her students will find their own passions and carry them forward into careers, whatever they may be.

“I want them to love and take care of their own bodies and their health, no matter what kind of bodies they have, or their gender identity,” says Higgins. “I want them to be critical consumers in their own health seeking, and I want them to be critical, in general, of how our society influences health.”